|

|

|

|

|

|

|

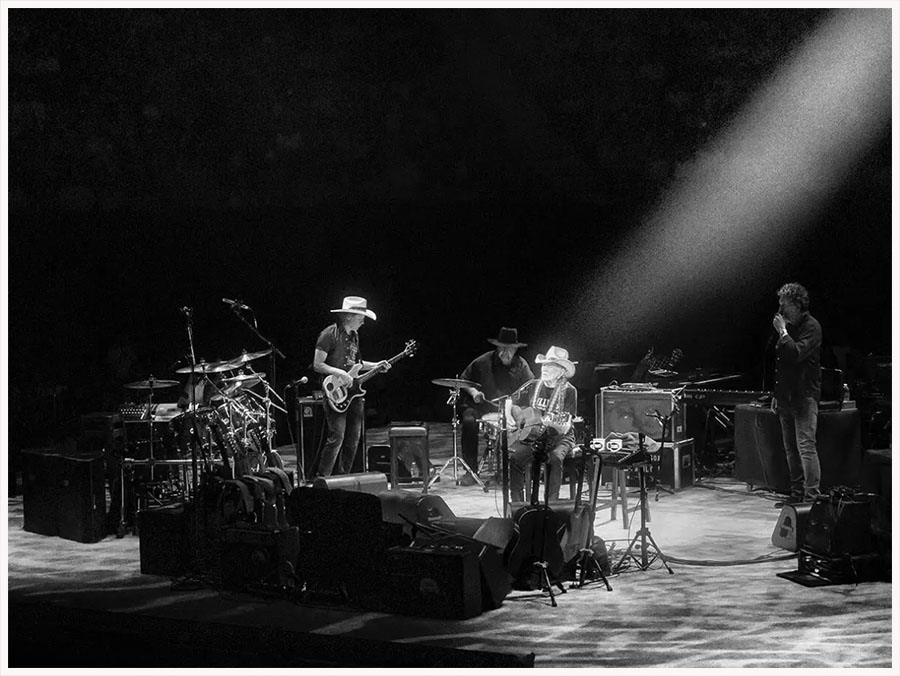

As he approaches 90, even brushes with death can’t keep him off the road — or dim a late-life creative burst.

By Jody Rosen -- Aug. 17, 2022 Willie Nelson has a long history of tempting, and cheating, death. In 1969, when his home in Ridgetop, Tenn., caught fire, he raced into the burning house to save two prized possessions, his guitar and a pound of “Colombian grass.” He has emphysema, the consequence of a near-lifetime of chain smoking that began in childhood, when he puffed on cedar bark and grapevines, before turning to cigarettes and then — famously, prodigiously — to marijuana. In 1981, he was taken to a hospital in Hawaii after his left lung collapsed while he was swimming. He underwent a voluntary stem-cell procedure in 2015, in an effort to repair his damaged lungs. Smoking has endangered his life, but it also, he thinks, saved it: He has often said that he would have died long ago had he not taken up weed and laid off drinking, which made him rowdy and self-destructive. Now, in his late 80s, he has reached the age where getting out of bed each morning can be construed as a feat of survival. “Last night I had a dream that I died twice yesterday,” he sang in 2017, “But I woke up still not dead again today.” Still, some close calls are closer than others. One evening in early March 2020, the singer and his wife, Annie, were sitting outside the sprawling log cabin residence at their ranch in Spicewood, Texas, in the Hill Country about 30 miles northwest of Austin. It was warm and clear. The sun was going down. “We were watching the sunset,” Annie recalled not long ago. “And these little lights started to zip across the sky. The first one kind of flashed past in the distance. Then there was a second, which went by a little closer. All of a sudden, the light went right past us — like, two feet over Will’s head.” The couple scrambled into the house and got down on the floor. According to Annie, the neighbors were “having another one of their gun parties. Apparently they got drunk and left a bunch of kids with semiautomatic rifles.” The police, she said, explained that the lights came from tracer bullets. “I said, ‘Are those even legal?’ But of course, nuclear weapons are legal in Texas. I told the police to please just pass along this message: ‘Dude, you don’t want to be the one that kills Willie Nelson. Especially in Texas.’” “Anyway,” she said, “that was the beginning of our Covid quarantine.” |

|

Days earlier, Nelson played for a crowd of more than 70,000 at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo. Now cities were going into lockdown. Given Nelson’s age and underlying conditions, a deadly virus that attacked the respiratory system was a frightening proposition. So the Nelsons hunkered down in Spicewood, where they were joined by their adult sons — Lukas and Micah, both musicians — and Micah’s wife, Alex. For the first time in decades, Willie Nelson was staring at an empty calendar. For several months, only Annie left the ranch, once a week, to buy groceries. Nelson and his sons played lots of poker, dominoes and chess. Nearly every evening, the three would gather in the living room with their guitars to sing Nelson’s songs and old favorites by the likes of Hank Williams and Roger Miller. “It kept us sane, sort of,” Lukas says. “My dad was bored. He was anxious. He was in a state of existential dread, fearing that this thing he’d done his whole life would never come back.” Nelson tried to keep busy, meeting with a physical therapist for online sessions, sitting for Zoom interviews and performing livestreamed benefit concerts. But his famous tour bus sat by the entrance to the ranch, uncharacteristically idle. Nelson has spent much of his life on tour buses, answering the siren call of the Interstate and the concert hall. “I can’t wait to get on the road again/The life I love is making music with my friends,” he sang, decades ago. There are thousands of songs about roving troubadours, but “On the Road Again” must be the most joyful and unabashed. For Nelson, barnstorming the country with a hot band is pure freedom. There was a moment, in the 1990s, when he pulled himself off the road, signing a contract for a six-month residency at a theater in Branson, Mo. But his cabin fever grew so acute, he wrote in his autobiography, that he took to “pitching a big sleeping tent in my hotel room and pretending I was out in the woods.” Read the complete article at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/17/magazine/willie-nelson.html?te=1&nl=the-great-read&emc=edit_ts_20220817 willie220820 |

|

... ... |